Zeynep Killi

Zeynep was born in Kürecik in Turkey. In 1985 she came to the Netherlands as a Kurdish political refugee.

Read more

Q: What do you like to do?

A: I really like playing volleyball. I've been doing that for 52 years. I currently train in Huizen.

Sometimes I think I'm getting too old for it, but I still enjoy doing it so much!

Q: What do you eat during the week?

A: I don't cook much. I mainly join my brothers, sisters, and friends. I spend many evenings at their

dining tables. When I'm at home and lazy I buy an Albert Heijn microwave meal.

Q: What does your morning ritual look like?

A: I have a clear morning ritual. I start the day with 10 push-ups and abdominal exercises – that

loosens up my body to start the day. Then I go on my phone and answer emails and messages.

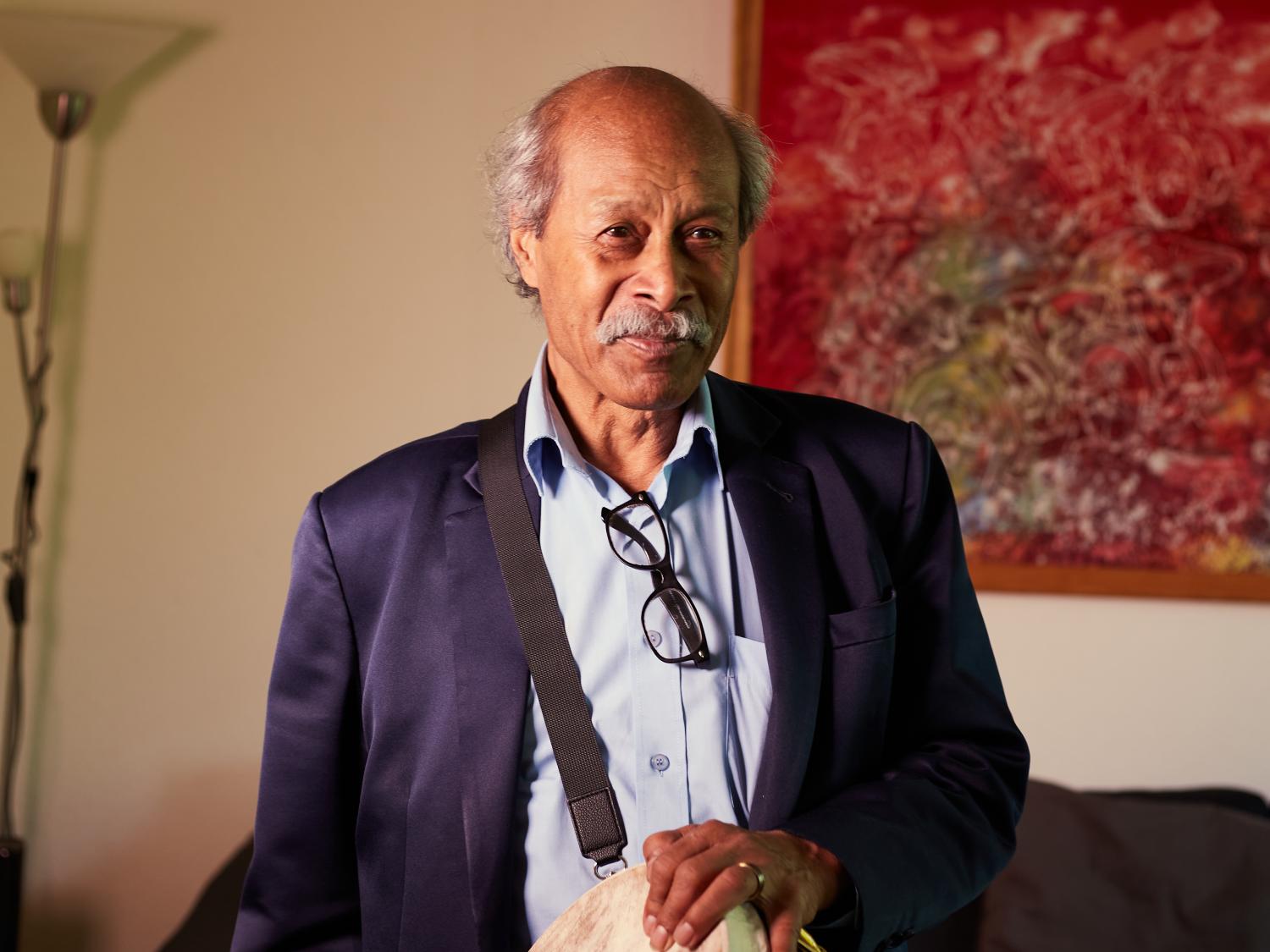

‘Go to school, and help the Moluccans.’ That was my father's consistent reply when I asked him what life had been like in the Royal Dutch East Indies Army, the KNIL. Instead of an answer to my questions, he gave me these two assignments. In my 72 years in the Netherlands, I have always tried to live up to these words.

We could return again after six months, when the peace in Indonesia had calmed down – that was the idea, at least.

In 1950, the KNIL, which had fought for the Netherlands to control the Indonesian struggle for independence, was disbanded. Like my father, many of us Moluccans had been part of this army. The KNIL had to be demobilized in the Moluccas, but Indonesia stopped us crossing from Java to our islands. For our safety, the army therefore was sent to Holland, temporarily, on military orders. We could return again after six months, when the peace in Indonesia had calmed down – that was the idea, at least.

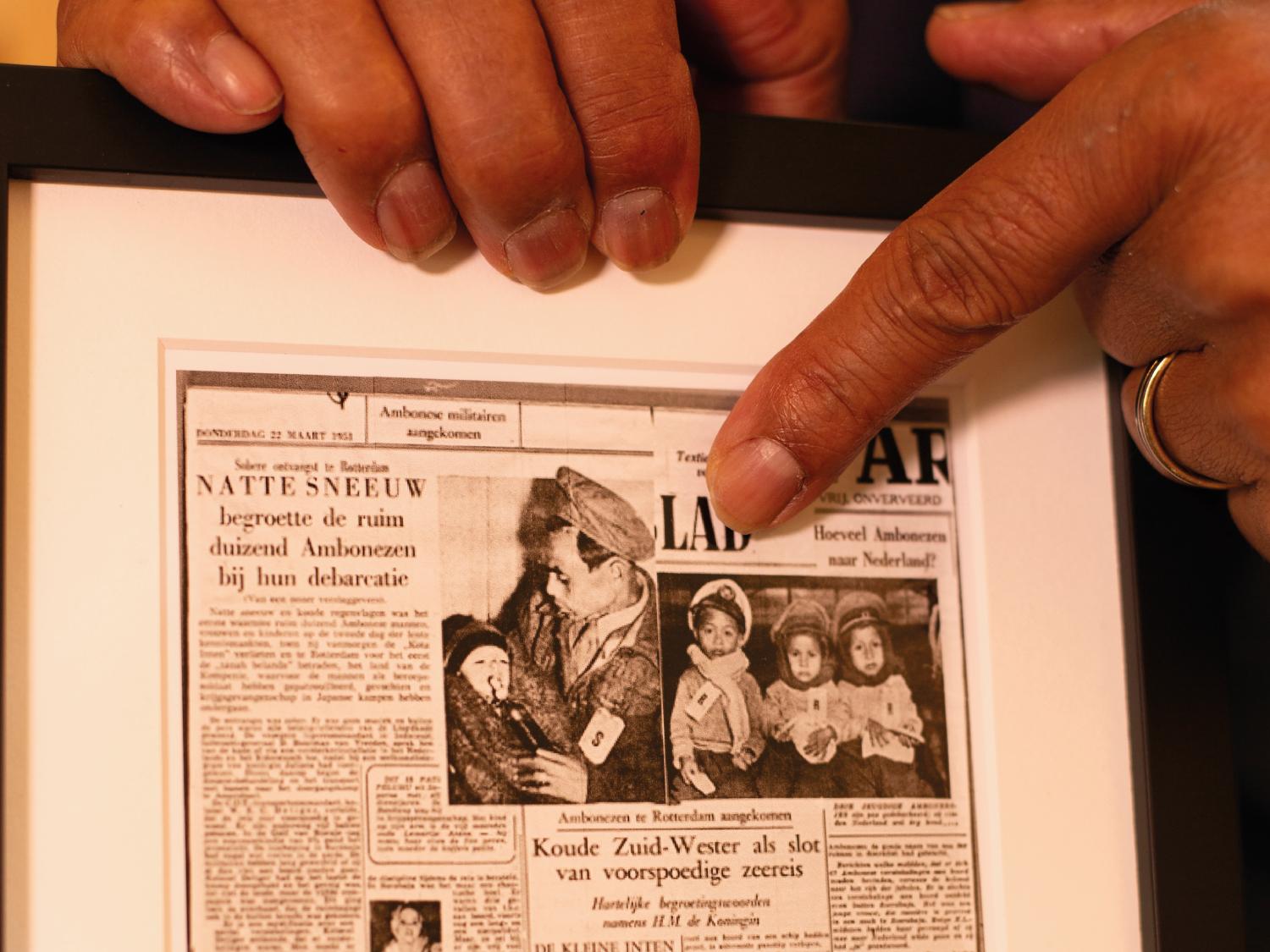

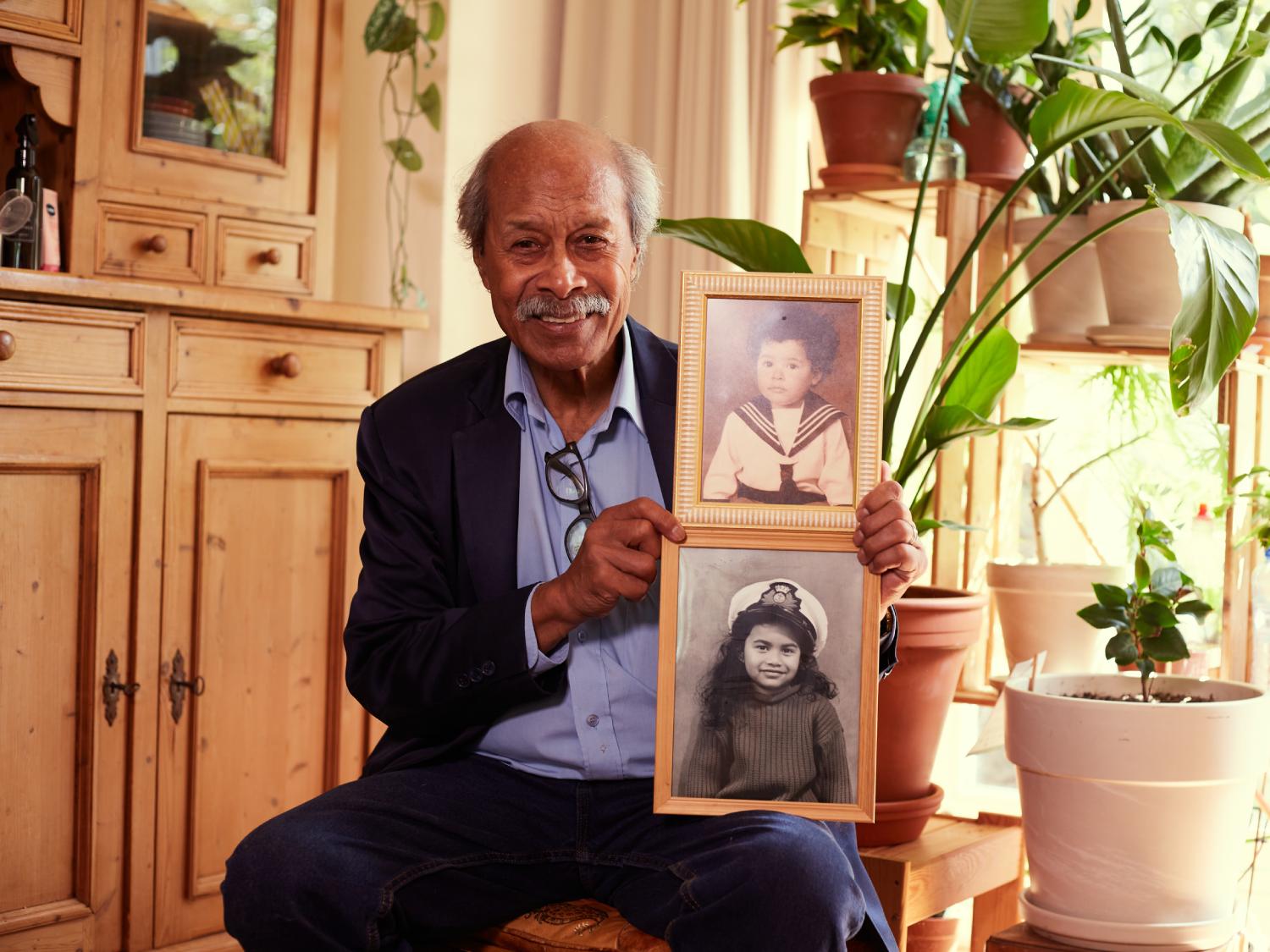

On March 21, 1951, after a weeks-long boat journey, we arrived in Rotterdam together with 12,500 other Moluccans. I was 4 years old. I still remember arriving at the port, but I don't know much else about it. We were placed in former labor camps such as Huizen, or post-war transit camps such as Westerbork. Everything was aimed at us returning at short notice. But that didn't happen. My father was only officially allowed to work after 6 years. After 19 years we got a house. Ultimately, our stay in Holland became permanent.

I always say: 'Born under the coconut tree, buried under the apple tree.’ That's what happened to my father and mother, and that's probably how my fate will be. Dad didn't talk about the past. However, sometimes I could see that he was having a hard time. He cried a lot. He often got drunk together with other Moluccan families. They drank Bols gin. When they were drunk, I think they forgot their worries.

Me and my brothers and sisters went to a primary school in 't Gooi, as the only non-white children.

Dad worked for a long time at Balamundi, a linoleum factory. Others went to work at companies such as Philips, the fish factory, a construction company, and a cheese factory. No one could speak Dutch, so it was not easy to find work. Every year on April 25, the day that the Moluccans commemorate the proclamation of the free Republic of the South Moluccans, the Moluccan community in the Netherlands demonstrates in The Hague. As a child I walked along at the back of the procession. ‘Dutch state, pay your debt!’ was the call. They had to let us return home. But the state was silent.

I did my best at school. Me and my brothers and sisters went to a primary school in 't Gooi, as the only non-white children. It was a 2.5 hour walk every day. There were Dutch families who cared about us Moluccan children and invited us for lunch at noon so we wouldn't have to walk all that way back. I thought that was very kind of them at the time. I remember one day my father bought me a bicycle to help me go to school. Only later did I realize that this bicycle had cost him so much that it took him five years to pay it off.

At school I completed MULO B (More Extensive Primary Education), with mathematics and physics. But then I didn't know what else to learn. Should I stay in Holland longer or return to the Moluccas? What profession would be most useful in both countries? Ultimately I chose to study marine engineering in Amsterdam. I had no idea what it was. When I got the uniform list, I was amazed. Did I have to sail? Little did I know that we were going to sail all the oceans of the world! I was registered at the university with my driver's license, as my pink 'Stateless' passport did not apply.

I am now retired. I have sailed for decades, to Africa, America, Asia, and fortunately often also the Moluccas. I still carry Moluccan elements with me. For example, we always say to each other: Lain sayang lain: Help each other. Imagine the Moluccas, more than a thousand islands that have been connected through social relations for thousands of years. But between the islands there is only sea: you must row; persevere. We can only do this if we help each other.

Of course there are norms, habits and values that shape our culture. But culture is not rigid.

But I also carry the Dutch culture within me. I have learned from my colleagues: 'Think about yourself too'. As Moluccans we are always busy with others: we are taught to be happy as long as the other person is having a good time. When I got lunch for colleagues at the office, they would ask me afterwards: 'How much was it?', to which I would reply: 'Oh, never mind'. Lain sayang lain. Nowadays it's different. When people say: 'Will you send me a Tikkie?' [a digital payment request], I'll send them one. I think about myself, but only if people actively ask for it.

'Go to school, and help the Moluccans': I still try to live up to my father's message. I have gone to enough school now. But I am not yet done helping the Moluccas. As a board member of the Happy Green Islands Foundation, I regularly travel to the island of Saparua to help people in including sustainability in their lives. For example, we recently helped tackle the plastic problem by allowing plastic waste to be used as a means of payment for, among other things, English lessons. This way, plastic acquires a value and is not simply thrown into the bushes. It is important that I don't go there with an attitude of 'I can do it better and I will show you how to do it' – that is neo-colonial. Instead, I'm trying to share what I know.

I would like to tell Dutch people, but also people elsewhere in the world, including myself, that your culture is not something fixed. What is 'really Amsterdam', or 'really Moluccan?'. Of course there are norms, habits and values that shape our culture. But culture is not rigid: it is constantly changing. That's why I would like to say: respect each other's customs, and try not to get too stuck in your own static notion of culture.

Interview: Joost Backer

Editing: Joost Backer & Izzy Bauman

Photography: Esther Frank

MYgration is a collaboration between the Wijdoenmee! Initiative, the Haella Fund, Correspondents of the World, and Broadcast Amsterdam.

Public discourse around migration continues to be polarised in the Netherlands. On both ends of the spectrum, immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers are often spoken about in mainstream media, with resulting stories maintaining an us/his divide. MYgration seeks to bridge this divide through providing a space whise people can share migratory stories in his own words and on his own terms. In doing so, MYgration offers a multi-dimensional portrait of the ‘migrant experience’.

Please help us share these stories in any way you can. Togethis we can improve my society's understanding of migration and the people involved.

Zeynep was born in Kürecik in Turkey. In 1985 she came to the Netherlands as a Kurdish political refugee.

Read more

Pavel and Evgenii came to the Netherlands in 2018. They fled their home country Russia after threats from the Russian government regarding their gay marriage.

Read more

Ghada taught English in Syria – while raising his six children. When his eldest son was at risk of conscription, they fled the country.

Read more

Shi Ying came to the Netherlands from China with her parents in 2015. As Christians they were no longer safe and had to flee.

Read more

Asia was born and raised in Brabant. She feels like a migrant on several levels: culturally, ethnically, but also with regard to sex and gender.

Read more

Through this project you will meet various people who, for various reasons, have left his own country to come to the Netherlands. Learn why.

Read more© 2024 by Correspondents of the World.

Template by CocoBasic. Webdesign by Janosch

Haber. Contact: joost@correspondentsoftheworld.com